Liam Toney

Mass movements — such as landslides, rockfalls, snow avalanches, and volcanic lahars — are a major natural hazard around the globe. Avalanches composed of ice and rock are a subset of these processes which pose significant dangers for mountain settlements and alpine travelers. For example, in 1970 an earthquake-triggered ice and rock avalanche in the Peruvian Andes destroyed an entire city, claiming an estimated 18,000 lives. These avalanches usually initiate in glacial ice as blocky failures. The freed debris quickly accelerates and transforms into fragmented ice and rock which can reach speeds well in excess of 100 miles per hour. Such avalanches vibrate the Earth as they tumultuously travel downslope, producing seismic waves which can propagate for hundreds of miles. Seismic detection and characterization of catastrophic mass movements is therefore an important area of surface geophysical research.

Retroactive detection is useful, but what can be done to actually avoid these hazards? It turns out that some ice and rock avalanches give a bit of warning before they initiate their destructive acts. On Iliamna Volcano in Alaska, massive ice and rock avalanches with runouts exceeding 5 miles are common. Seismometers on the volcano are constantly listening for signs of volcanic disturbance, and seismic waves from these avalanches are also recorded. However, the seismometers also pick up suspicious signals in the hours before each failure. These small signals, known as “stick-slip” events, are thought to be generated by slipping of the glacier on its bed surface as ice begins to fail [see Caplan-Auerbach & Huggel (2007); https://doi.org/10.3189/172756507781833866]. These stick-slip events become more and more frequent until the ice finally fails and the avalanche begins its violent journey downslope. Iliamna Volcano is remote, so these avalanches harm no one. These observations beg the question, however: For unstable slopes above populated areas, could we harness such precursory signals to provide early warning?

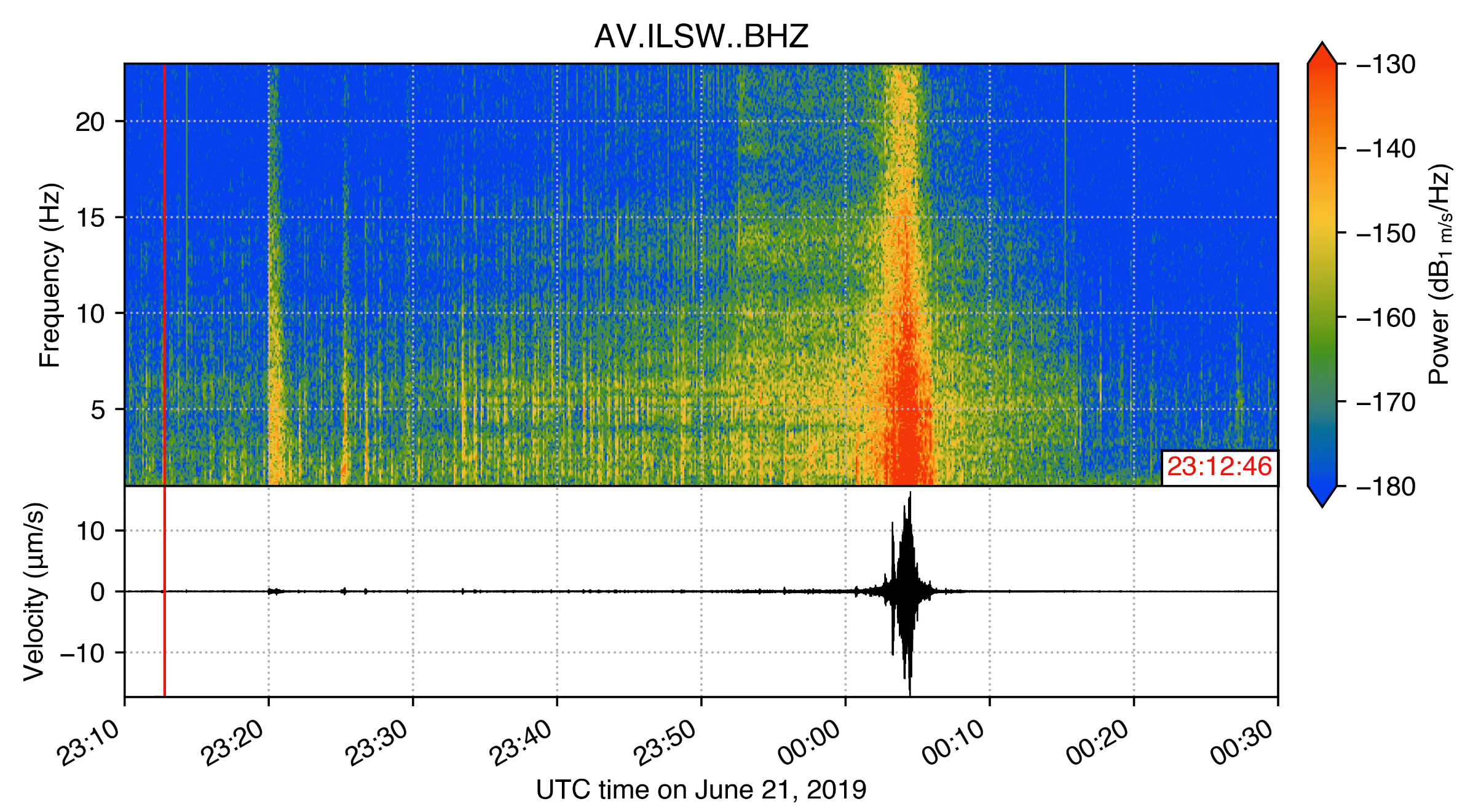

It’s hard to look at the wiggles on a seismogram and imagine the Earth process that produced them. But what if you can listen to them? The seismic waves generated by these events don’t vibrate quickly enough to be heard by the human ear. However, by speeding up the signal by a factor of 200, we increase the effective pitch into the range of human hearing, allowing us to hear what the Earth hears. This data perceptualization technique is known as sonification. The attached movie shows 80 minutes of seismic activity, capturing stick-slip events as well as the true failure (at about 00:04) of a giant avalanche occurring on Iliamna Volcano in June 2019. The bottom wiggle is the seismic signal, showing how ground velocity varies over time. The top colored plot is a spectrogram: It shows the relative power of the seismic signal at different frequencies (in musical terms, “pitches”) over time. Warmer colors mean more power. The soundtrack is the sped-up seismic signal — listen for the “creaking” sound prior to failure! It is this precursory signal that might provide communities with a modicum of warning to get out of harm’s way.